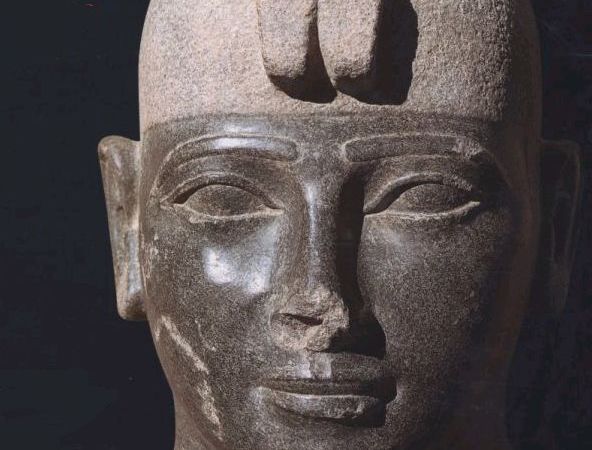

Those who have followed Sudan’s revolution closely have heard Alaa Salah’s rendition of Sudan’s revolution song, which calls out both the Kendaka, Sudan’s famous Warrior Queens, and Taharqa, the most famous of the Nubian Pharaohs. I very much appreciate the return of the Kandaka to her rightful place in Sudan’s revolutionary history. I give thanks and praises to all of the Kandakas in my life. But my man Taharqa, mentioned in the same song, needs a little appreciation, too.

What if I told you one of the most militarily powerful Pharaohs in history was from the land that is modern-day Sudan? That he was black, Nubian, and saved Jerusalem from certain destruction? You would probably say that I was crazy and that the revolution has gotten to my head. Maybe it has, but let’s look at history.

The 25th Dynasty Nubian pharaohs united the Nile Valley from the Delta to Kush in modern-day Sudan and led a revival of the culture and its intellectual and artistic roots. The first was Piankhi, who ruled Kush from between 743 and 712 BC. He mobilized his famous Nubian archers and moved north through cataracts and defensive Egyptian forts, down the Nile. City after city, all the way to the Delta, his archers were victorious over the old oppressors or invaders from Libya or the Levant. He saw himself as on a mission to restore the true faith, ordering his soldiers to ritually cleanse themselves and seek the favor of the gods before each battle. This set the stage for the Nubian monarchs Shabaqo, Shebitqo and his cousin Taharqa, who ruled from 690 to 664 BC. Whereas Piankhi focused on restoring the cultural, spiritual and intellectual roots of an ancient civilization that had gone into decline, Taharqa spread the revitalized culture through military conquest.

Taharqa’s reign was the most glorious militarily, expanding Nubian influence from Libya in the West to Phoenicia in the East and north to the Mediterranean. It was through Taharqa’s conquests this that parts of the Levant, particularly Jerusalem, Palestine, and Lebanon, became protectorates of Nubia and Egypt. Taharqa maintained strong bonds between Egypt, Lebanon, and Palestine. The large Jewish community in lower Nubia, at Elephantine Island, may have played a role in this alliance with their brethren in Jerusalem.

Taharqa is the only Pharaoh to be mentioned by name in the Bible. As the Old Testament recounts, there were constant battles between Assyrians and Jerusalem. The Jewish King Hezekiah of Jerusalem came under attack from the Assyrian king Sennacherib who was advancing towards Tyre (in Lebanon) with vastly superior forces. He called his friend Taharqa. As explained in Isaiah 37 8-9, “Rabshakeh returned and found the King of Assyria warring against Libnah. Now Sennacherib received word that Taharqa, the King of Cush, was marching out to fight against him.” The Assyrian reminded Hezekiah of the fate of other kings that took on the Assyrians. Truth be told, the Assyrians were the most fearsome fighting force in the world at the time.

My man Taharqa had other ideas, and also had with him the Nubian archers, whose accuracy was legendary. Isaiah 37:36-37 explains that “the angel of the Lord went out and put to death 185,000 in the Assyrian camp. When the people arose the next morning, they were all corpses, and Sennacherib withdrew to his capital.” Nubian support proved decisive, and Sennacherib failed to capture Tyre, and Jerusalem was saved. Isaiah, King of Israel, gave gifts to the Taharqa in recognition of his support.

The historical record is that Taharqa, as protector of Jerusalem, reinforced Hezekiah against the Assyrians in the Battle of Eltekh. This particularly audacious battle that occurred when he was 20 years old, the favorite of his grandfather but not yet Pharoah. This was a decisive victory, but the fighting against the Assyrians created a potent enemy. The Assyrian king learned that the way to capture Jerusalem was to defeat Nubia.

Many years later Sennacherib’s son crossed the Sinai and attacked Taharqa’s troops with a massive number of soldiers at Memphis. Taharqa suffered a catastrophic defeat, including the capture of his wife and son. Taharqa was wounded five times but escaped and retreated. He later successfully regained Memphis, but was defeated a second time and finally fled to Napata, in Nubia, in 674 BC. The subsequent Assyrian invasion of Egypt ended the era of Nubian Pharaohs in Egypt. Nubians still ruled a vast area from Aswan to the fourth cataract.

So what are the lessons for today?

The first is about the fact that you did not know much of the above. Why? Because Sudanese have never written the narrative about their history, and few understand the importance of Nubia or Sudan. I just attended an exhibit about Egyptian Queens at National Geographic, and while it did an excellent job describing Nefertari, Tiye, and the like, it made no mention of the Nubian Warrior Queens – the Kandakas – just a little further south and in some cases more powerful. It is as if they didn’t exist.

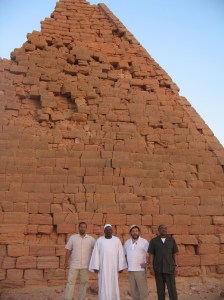

Much of the region’s ancient history was written by Egyptologists. George Reisner, for example, excavated Kerma, the Gebel Barkal temples, and the royal pyramids of Kush. He was able to decipher the names and dates of the kings of Kush over 1,100 years from the 8th century BC to the 3rd century AD – a staggering achievement. He unlocked the study of Nubia. But Reisner himself could not escape the worldview that Nubia was a peripheral part of Egyptian culture rather than its own civilization. Many of these historians approached their work with the assumptions prevailing early in the 20th century, particularly about the agency and capability of black Africans to build a sophisticated civilization. Africa was at the time a source of slaves, in the European mind the heart of darkness, while at the same time Howard Carter was discovering the dazzling tomb of Tutankhamun and the beauty and complexity of ancient Egypt.

The world has changed. Stones tell no lies, the record is being set straight, and now, finally, Sudanese are shaping their own narrative.

The second lesson is best captured by TLC’s song, Don’t Go Chasing Waterfalls. Now, Taharqa was one hell of a warrior, and he had the baddest archers the world has ever seen. Jerusalem – as an alliance partner and a friend, was worth protecting. But taking on battles in the Levant, against an enemy with a more significant population, made Nubia a target. This, decades later, led to the end of the Nubian reunification of Nubia and Egypt, which was a successful revival of culture and the arts (if you visit Karnak you can see this first hand). It wasn’t internal corruption, bad harvests, or a political intrigue that ended Nubian rule. It was revenge – in the form of an invasion by an enemy whose anger was passed from one generation to the next over decades.

So then one might ask, why is Sudan now fighting in Yemen? Why is anyone fighting in Yemen? Sudan has problems of its own… please stick to the rivers and the streams that you’re used to.

Thawra!