Jeffrey Sachs, Director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, wrote in an August article that We are all Climate Refugees Now. “This summer’s fires, droughts, and record-high temperatures should serve as a wake-up call.” he wrote. “The longer a narrow and ignorant elite condemns Americans and the rest of humanity to wander aimlessly in the political desert, the more likely it is that we will all end up in a wasteland.” His point is that the politics of climate denial is leading us into a new era which poses grave risks to humanity, including mass migration.

What does this have to do with Nubia?

The Nubians were the first climate refugees, and have a lot to teach the world, as I explore in my upcoming book: The Water Wheel: Reflections on a Submerged Culture and Identity.

The signs have been there for all who wish to read them.

In 2011 Thailand experienced a flood that was the fourth costliest natural disaster in history at the time, and cost over 800 lives. In 2013, virtually every building in Tacloban, in the Philippines, was wiped out by a four-meter wall of water that surged over the city during typhoon Haiyan. The cost of the Thai flood was eclipsed by hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, which has now exceeded $80 billion in economic damage and killed over 4,000. The United States experienced $300 billion in damage in 2017 and is going through a string of devastating events, including New Orleans, Houston, New Jersey/New York, and California wildfires.

The worst has yet to come.

Sea level rise is expected to continue for centuries. In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projected that sea levels would rise 18 to 59 cm during the 21st century. In 2013 IPCC raised its estimate to 28 to 98 centimeters by 2100, 50 percent higher than the 2007 projections. The Third National Climate Assessment, released in May 2014, projects a sea level rise of 1 to 4 feet, over 120 centimeters.

What is clear from these estimates is that not only will our storms be more violent, but also rising seas, and many of our coastal communities will need to relocate. In 2017 water and fish sloshed through the streets of Miami, whose existence is threatened, and climate change has already impacted its freshwater aquifer. Alaskan communities and Pacific Islanders are confronting the need to move to remain viable as people. Kiribati has prepared to relocate its population, but we should really be concerned for Bangkok, Manila, Dhaka, Dakar, Saigon, Rio de Janeiro, and Venice, both in Italy and Los Angeles.

There are parallels and lessons.

In 1964 over 100,000 Nubians were relocated, against their will, from the homelands in which they lived for over 5,000 years to make way for a massive lake created by the Aswan High Dam. Despite the immense importance of the region in history, and that it had not been fully explored by archeologists, the dam was the final straw, after three smaller dams earlier in the century, that ultimately shattered the way of life of my grandparents and their fellow Nubians. My father’s village is under 60 meters of water, and this blog was written to document the journey my son and I took to understand what happened.

There were more rational alternatives and ways to meet Egypt’s needs more sustainably. But dam had become a political imperative, a political symbol of a strongman’s desire to make Egypt great again. Alternatives were off the table.

Nubia had a few years to prepare for the exodus, but until the threat was imminent, there was denial. The magnitude of the change was not fathomed, not absorbed, not internalized.

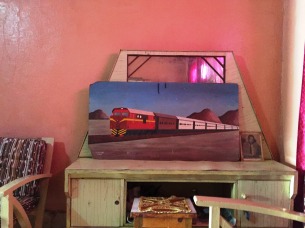

The displaced Nubians were initially given the power to choose among resettlement sites, and then the power was taken away. They had no input over the design of their habitat. For a community built on self-reliance, this was the deepest cut of all. They had no choice but to board the trains in 1964, to a destination not of their choosing.

The state tried to prepare, but wholly inadequately. They quickly build resettlement villages, each name replaced by a number; Nubian names replaced by Arabic names; the distribution of houses designed to favor the labor requirements of a state agricultural project, not the way people actually lived. Nubian houses in the old country were made of mud brick, painted and decorated, with beautiful courtyards, and since there was no rain, thatched roofs. These were considered worthless when compensation was offered; today they are regarded as priceless art, and their construction a perfect and sustainable adaptation to the natural environment. The houses that Nubians received? Years later, we discovered that the water supply was untreated and dangerous, and the “modern” roofs are made of asbestos.

This loss of agency contributed to denying Nubians the ability to lead lives informed by their full selves. The relocated Nubians, fifty years after the flood, are barely hanging on to a culture that persisted for five thousand years. The language is dying. The older generation remains understandably bitter, wedded to a paradise lost, their notions fixed in time and unyielding; unable to fully commit to a “New Halfa.”

Perhaps few who are displaced will have lost a civilization that existed continuously in a narrow parcel of land for over five millennia, but for every community, the loss will be as deep and as profound. A significant share of humanity’s cultural assets is located on coasts. What will come of our sources of culture and identity, when we collectively arrive, to paraphrase the late Sudanese novelist Tayeb Salih, at our Season of Migration to the North?

Will the old canals of Bangkok, long since covered up to make way for roads and highways, flow again with water against abandoned sidewalks? Will the old shop houses, bridges, and the skyscrapers peer out from the water like the minaret of the central mosque of Wadi Halfa, a haunting last reminder of our collective failure, until finally giving way to the flood?

Until the urge to maximize at all costs is replaced by a call for balance, our past and our future are lost. The world is already experiencing a forced displacement crisis of historic proportions. Syrians, Africans, Afghans, and others are streaming across borders in more significant numbers and far more difficult circumstances than the Nubians who were forced to board trains and rebuild their lives 600 km away in 1964. Among other factors, a severe drought drove Syrian farmers to abandon their crops and flock to cities, helping trigger the Syrian civil war.

As more and more join the exodus, they will, like Nubians, inevitably confront a profound crisis caused by the contact between the rooted and the rootless. If the present path continues, that will be many of us. We are that Syrian child rebuilding her sense of confidence in a youth shelter; the Darfuri boy risking a Mediterranean crossing; the Brexit voter; the Afghan engineer seeking any employment whatsoever.

The modern climate challenge is not only about making agriculture productive in the sweltering heat or preventing our bridges and homes from being ravaged by the untamable forces that we have unleashed. The modern challenge is how to know one another. And to do so peacefully, without regret or loss of who we are.

In a world of transition and migration, this inevitably includes respect for the identity of the hosts as well as the guests. To join a new society and to be accepted, one must also contribute. In today’s world, the most significant contribution is that of ideas. Syria was the center of ideas; home of the world’s most extensive libraries and sources of knowledge, including optics, astronomy, much of medicine, and the scientific method itself. Nubia was a sophisticated civilization that both rivaled and renewed ancient Egypt, contributed extensively to Sudan’s history and was considered a model of peace and sustainability. Yet these contributions are not appreciated, not sought. As the wellsprings of our identity and our ideas are flooded, on what basis will the uprooted contribute?

There was a better way forward. These questions and some possible answers are explored in The Water Wheel: Reflections on a Submerged Culture and Identity. The book is with literary agents. Stay tuned.

The Photo is courtesy of Hassan Dafulla, the late Governor of Northern Province at the time of the Nubian Exodus.