African cities, particularly in countries touched by conflict, tend to sprawl as waves of the innocent, dislocated and displaced seek refuge along its borders or new lives within it. As we approach Khartoum, it is hard to tell if we’re actually in the city, whose outskirts have been growing for decades, until we’re in the middle of the chaotic traffic, fast food places, neon lights, and see planes descending into one of the world’s few downtown airports.

Having been to the place to which Nubians were resettled, our aim is to see the land we’ve heard about since childhood but never seen, the place where our grandmother used to swim with her friends in the Nile as her mother and father worked the land. I’ve seen pictures of the top of the minaret above the waterline, holding its head above water for a last breath before succumbing to the flood. We’ve spoken to those who took those fateful trains to their new land. But we’ve never walked on the land or breathed the air from which they were removed.

Wadi Halfa is 580 miles to the north. Khatir wisely decides to change the tires, oil, and brakes. We adjust our plans and join Wagdi for breakfast before heading out. He also sends with us food for the journey for which we are grateful and later enjoy. Tariq stocks up on Doritos, which amazingly are found in Khartoum.

As we head north from Khartoum, we are immediately are immersed in the traffic that is in part a legacy of the British, who thought it best to lay out Khartoum in the form of Union Jack. We cross a bridge near where the Blue Nile, which has descended from the mountains of Ethiopia, meets the White Nile which has meandered slowly up from Lake Victoria through South Sudan. The two rivers marry here and begin a journey as one to give life to Northern Sudan and Egypt. We head out through Omdurman, the center of so much of Sudan’s history, including the headquarters of the descendants of the Mahdi who led a nationalist uprising against Egyptian and British rule in the 19th century.

As we emerge from Omdurman it is already past noon. We take guesses as to the time we will actually arrive at the Wadi Halfa milestone 924 kilometers to the north. Tariq, more of a realist than I, guesses 20 hours to my 14. Amir, who guesses 10 will be the closest.

Whereas the road to New Halfa went through farms and villages, the scenery on the road to Nubia is dramatic in its stark emptiness. The black asphalt road stretches out in front of us, straight as an arrow. The sun beats down intensely. The milestones alternate, left and right, and count out each kilometer like giant footsteps. There are no herds of anything except high voltage power lines and mobile phone towers powered by the sun.

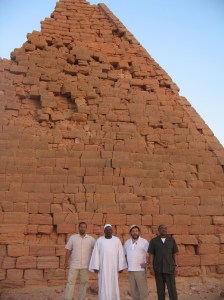

Due to the late departure from Khartoum we decide not to stop at Meroe, the site of 64 Sudanese pyramids I visited maybe five years ago along with Ibrahim Elbedawi, Musallam, and Alan Gelb in the photo. But I’m determined to see Kerma, one of the world’s earliest organized cities which flourished from around 2,500 BC. Kerma is one of the three capitals of the series of Nubian kingdoms that vied for control of the Nile Valley.

Due to the late departure from Khartoum we decide not to stop at Meroe, the site of 64 Sudanese pyramids I visited maybe five years ago along with Ibrahim Elbedawi, Musallam, and Alan Gelb in the photo. But I’m determined to see Kerma, one of the world’s earliest organized cities which flourished from around 2,500 BC. Kerma is one of the three capitals of the series of Nubian kingdoms that vied for control of the Nile Valley.

Tariq asks for a “nature break” and the rest of us, who had been holding back, readily agree. We step out into the wilderness. As far as the eye can see, it is the tan sand of the Nubian desert; a barren landscape with dramatic rock formations jutting into the sky. The wind-whipped air is pure, clean and dry.

As I return to the car, the shadow is of an elephant.

We are passed by a series of trucks carrying camels in the back. For centuries this route has been taken by camel traders who ride for forty days to sell their livestock in Egypt. Now they ride in an open truck, appearing to enjoy the journey, staring off into the distance. Two are clearly arguing over space.

After cutting through the desert for hours, we see that the road has approached the river. This is evident because of the groves of date palms that grow on its banks stand in sharp contrast to the surrounding desert. Where there is water, there is life.

We stop to refuel and find a group of German tourists in a convoy of land cruisers who are touring the archaeological sites of Northern Sudan. They have stopped to have tea in a roadside open air café. Some of the Germans are having an animated conversation with the waiters. I have some sweet aromatic coffee, spicy with the taste of cardamom and clove.

We pull off the main road into a village to start asking directions. Amir, who has joined us from New Halfa, starts asking directions in the Nubian language, and there is a connection. Each villager points us further down the road, deeper into the village toward the museum. We see kids going home from school, others playing soccer, neighbors on their doorstops talking to one another.

Finally, we arrive at the museum at Kerma. It is near sunset, and the guards are closing the museum and getting ready for the evening prayer. The doors are locked, but through the glass we see the statues found in 2003 on this site by a Swiss archaeological team led by Charles Bonnet; statues of the most famous kings of Nubia, including those of the 25th dynasty Nubians that conquered Egypt and became Nubian Pharaohs. But the museum is not the main attraction, it is the site itself.

Finally, we arrive at the museum at Kerma. It is near sunset, and the guards are closing the museum and getting ready for the evening prayer. The doors are locked, but through the glass we see the statues found in 2003 on this site by a Swiss archaeological team led by Charles Bonnet; statues of the most famous kings of Nubia, including those of the 25th dynasty Nubians that conquered Egypt and became Nubian Pharaohs. But the museum is not the main attraction, it is the site itself.

Kerma is remarkable. It was the capital of ancient Nubia, known in various periods as Napata or Kush from 2500 to 1500 BC. As early as the sixth dynasty (2,300-2,400 BC) there were diplomatic, cultural and economic relations between the ancient Egyptian capital city of Memphis, near modern Cairo, and Kerma,

It was a trading city, with homes for the wealthy traders and dignitaries that helped move the product north, east and west. Bonnet’s team found hundreds of seals that were remnants of concluded trade deals.

Over the next millennium, Kush’s power grew along with that of Memphis, a co-existence that included periods of cooperation, rivalry and conflict. Ancient Egypt and Kush vied for supremacy for millennia; Kush grew more powerful when Egypt was weakened by invaders from the north; Kush in turn grew weaker through its conflicts with neighbors to the south.

This site itself, Kerma town, is just over the fence, now closed.

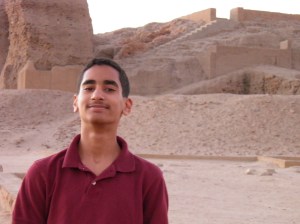

Deeply disappointed, we explain that we have been driving for seven hours to see this site; I explain that I would be happy even to look over the wall and taking a photograph, as you see above. With no argument at all, the guard casually mentions that the door 50 meters to the west is still open.

Tariq, Amir and I virtually sprint to the door, and run into the compound, a wide open space with what looks to be a large carved hill in the middle, with geometrically-patterned short mud walls throughout the area.

We climb the Deffufa, or main temple, and from above the view is astonishing: everywhere we turn, we see the outlines of the complex city that existed nearly 5,000 years earlier. It was organized hierarchically by a government that enforced urban zones including a religious sector with temples to worship deceased kings, royal residences, defense systems, and sectors for work, government and residence.

We climb the Deffufa, or main temple, and from above the view is astonishing: everywhere we turn, we see the outlines of the complex city that existed nearly 5,000 years earlier. It was organized hierarchically by a government that enforced urban zones including a religious sector with temples to worship deceased kings, royal residences, defense systems, and sectors for work, government and residence.

By 1750 BC, the kings of Kerma were powerful enough to organize the labor for monumental walls and structures of mud brick on which we stand today. They also had rich tombs with possessions for the afterlife; furniture, perfumes, pottery and food. On the death of a king hundreds of cows, and possibly some humans as well, were sacrificed to accompany the king on his journey.

The sun begins to set, and we imagine what life might have been like in 2,400 BC from this site, looking down not on ruins but on a thriving royal city. Thrilled and grateful for the experience, we return to the vehicle to resume our journey.

It quickly gets dark, and we our pace slows for our safety.

Near midnight, the sign for Wadi Halfa appears.

We have finally arrived.

Reblogged this on SHG: Sudan Information Hub.

LikeLike

Perhaps ending with “we have finally arrived”, would not do justice to “…500 year of detour”. I still loved it. But there must be more. What about the traditions of people living in those 500 miles? How people living in ancient lands look at modern day life? Its just that you left us wondering!

LikeLike